Lanyang Ming: A Retro Elegant Ming Typeface with Full Support of Taiwan Writing System

- justfont

- Role: Typeface Engineer

- Co-work with: Typeface Designer, Project Manager

- Tools: Glyphs, Python, Git

- Crowdfunding Project: https://wabay.tw/projects/lanyangming

- Official Website: https://justfont.com/lanyangming/

Drawing inspiration from the rich history of Ming Typeface (明體), designers were influenced by charms of obscure and ancient Chinese typefaces hidden within rare books to create Lanyang Ming (蘭陽明體). Lanyang Ming combines timeless elegance of Traditional Chinese typography with contemporary design principles, resulting in a vivid, warm, and expressive font that offers readers a poetic reading experience.

In addition to its special style, the most particular feature of Lanyang Ming is its support for OpenType ccmp feature, enabling full support for letters used in Taiwanese Hokkien (臺語), Hakka (客語), and indigenous languages (原住民族語).

Setting up and configuring these features was a crucial task of my work on this project. This process involved defining which glyphs needed to be composed and ensuring their correct display across various apps and software. It also addressed issues related to Unicode equivalence and normalization.

This work is essential for ensuring our font family accurately represent the full range of characters used in these languages, thereby supporting their continued use and preservation in digital era.

![]()

![]()

Minority Languages in Taiwan

In Taiwan, Mandarin Chinese (華語) is the primary language for daily communication. However, minority languages such as Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and indigenous languages are also officially recognized as national languages, showing the significance of preserving and transmitting these languages in speaking and written form.

Despite their official recognition, the development of writing systems for these local languages has long been neglected. This negligence has led to a lack of typeface and typesetting software capable of supporting the phonetic alphabets used by these languages.

Fortunately, with the recent emphasis on tradition culture and identity, more authors and publishers are beginning to embrace writing in their native tongues by using phonetic scripts. Moreover, development in OpenType technology and the unification of Unicode standards have further made the concept of writing as we speak a possible reality.

Lanyang Ming, a typeface designed specifically for use in Taiwan, satisfies these needs. It includes essential Latin letters, numbers, symbols, and over ten thousand Traditional Chinese characters. Additionally, we have taken into consideration the development of phonetic scripts that support the writing system of Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and indigenous languages.

Our company is deeply committed to preserving endangered local culture, and this dedication extends to the preserving and promotion of these minority languages through the development of usable typeface solutions.

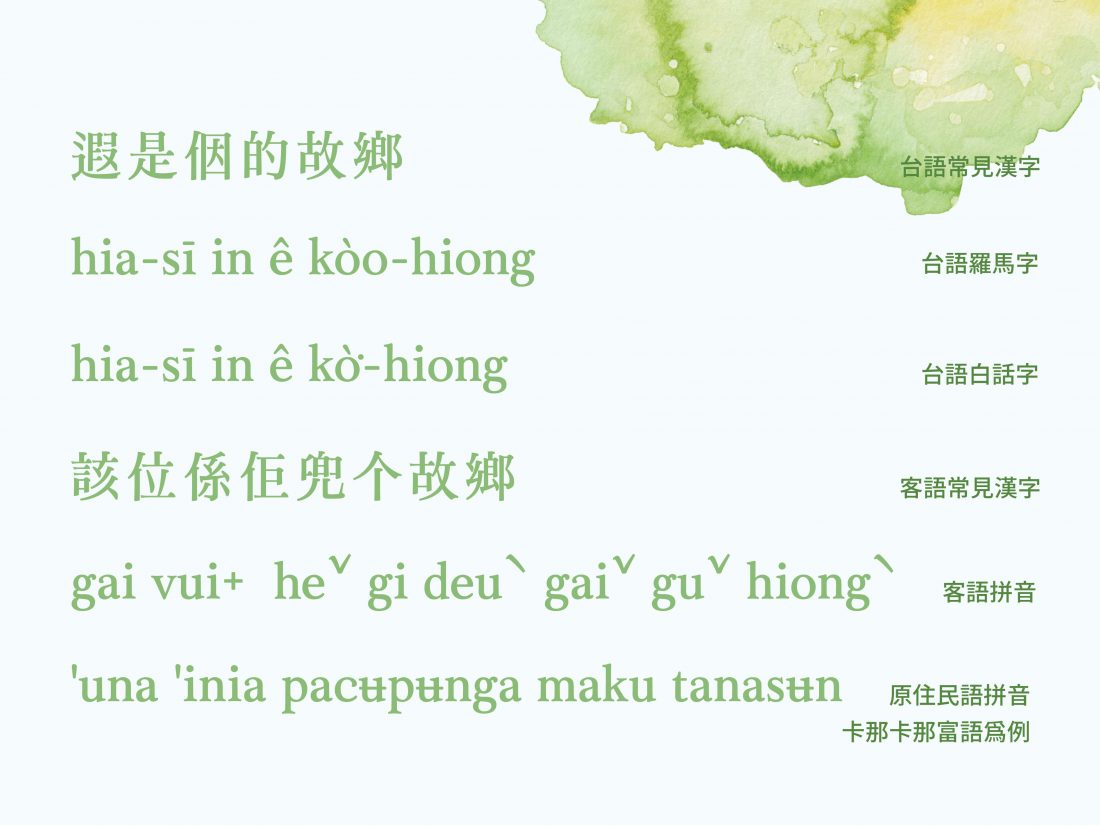

From top to bottom: Taiwanese Hokkien Chinese Character; Taiwanese Hokkien Tâi-lô; Taiwanese Hokkien Pe̍h-ōe-jī; Taiwanese Hakka Chinese Character; Taiwanese Hakka Romanization System; Kanakanavu Romanization System

Challenge of Phonetic Writing Systems in Digital Era

What kind of challenge arises with these phonetic writing systems?

Like most languages in Asia and the Pacific, Mandarin Chinese, Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka are all tonal languages (聲調語言). For instance, Mandarin Chinese has five tones (聲調), displayed in Pinyin (漢語拼音) as mā-má-mǎ-mà-ma, where diacritical marks above letter represent different tones.

The diacritical marks are similar to accents found in European languages, such as acute accent in French é or umlaut in German ü. However, tonal markers used in Taiwanese Hokkien and Hakka are more complex.

Take Taiwanese Hokkien, which has eight distinct tones, for example, there are two major phonetic systems, Pe̍h-ōe-jī (abbr. POJ, 白話字, lit. 'vernacular writing', a.k.a. Church Romanization) and Tâi-lô (abbr. TL, 臺灣台語羅馬字拼音方案, lit. 'Taiwanese Southern Min Romanization Solution'). The former includes five diacritics, while the latter includes six diacritics to represent tones. These phonetic systems require precise combinations of letters and diacritical marks to accurately represent tones.

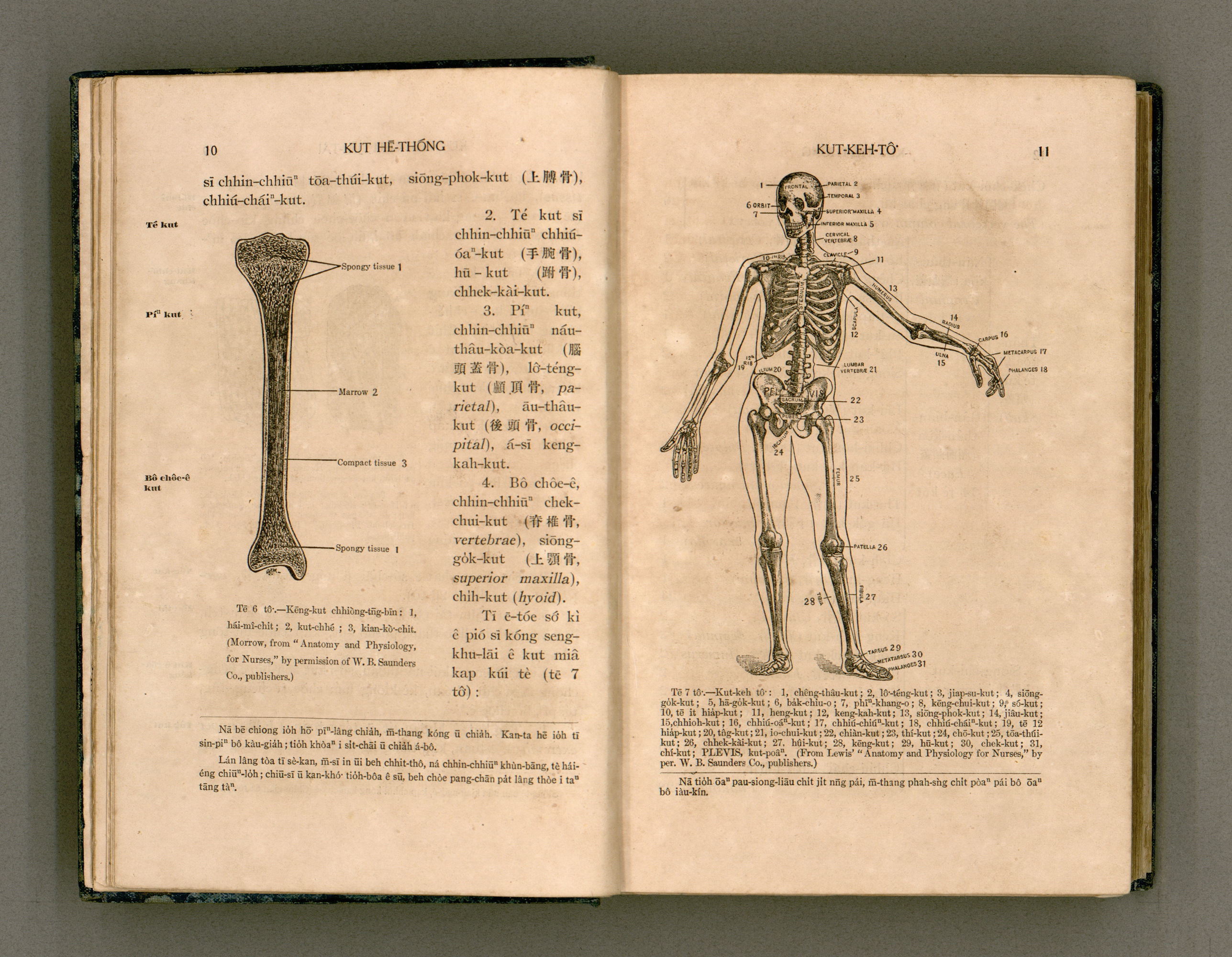

'Lāi Gōa Kho Khàn-hō͘-ha̍k' (lit. 'The Principles and Practice of Nursing'), published in 1917. The book was compiled by English M.D. George Gushue-Taylor and his Taiwanese assistant Tân Toā-lô, written in the Pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography and includes 40 chapters, 675 pages and 503 figures. (Source: Open Museum)

In Taiwanese Hokkien POJ, it use an o with an acute accent mark to represent /ə/ with a second tone, and another o with an acute accent and a dot above right to represent /ɔ/ with a second tone. The former o with an acute accent has its own unique Unicode code point, U+00F3, but the latter is not included in Unicode.

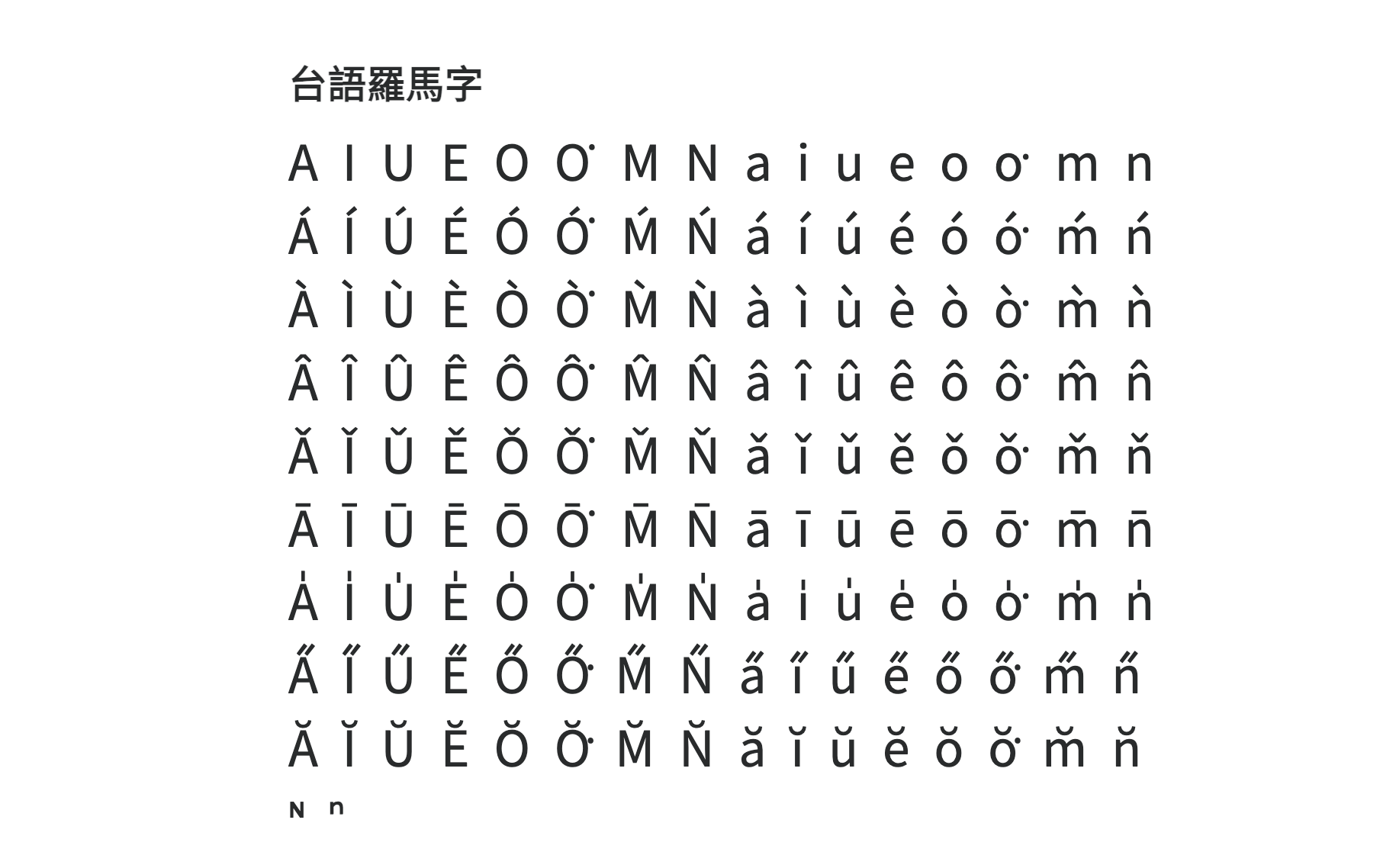

All alphabets of Pe̍h-ōe-jī. The sixth column and thirteenth column show o with a dot above right with eight diacritics. (Source: tauhu.tw)

Diacritical Marks and Unicode

We know that Unicode is the standard for computer encoding today. Thus, if a glyph is not included in Unicode, it becomes challenging to display and save.

When we look back to the history of modern computer, the development of ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) and EASCII (Extended ASCII) in the U.S. and Europe were focus on encoding the basic Latin alphabet for English, and accented characters for Western European languages.

As the shift from ASCII to Unicode, Unicode inherited this legacy by encoding characters used in European languages for compatibility. Initially, Unicode aimed to assign a unique code point to each letter, including basic Latin alphabet and its diacritical variations. For example, e (U+0065) and é (U+00E9) were given different code points.

This approach was achievable for Western European languages, where the number of accented characters was relatively small. Over time, as Unicode evolved into the global encoding standard, it became apparent that many languages worldwide, particularly those using Latin-based alphabets, required additional accented characters. Some were borrowed from existing languages, while others were newly created to meet specific phoneme (音位).

Take the umlaut (two dots) for example. In German, the vowels a, o, and u take an umlaut above them, becoming ä /ɛ/, ö /ø/, and ü /y/, and these are encoded in Unicode. Similarly, characters like i / ï (used in French, Afrikaans, Catalan, Dutch, and other languages) or e / ë (used in Albanian, Kashubian, Emilian, and others) are also encoded. However, an umlaut on consonants like c / c̈ and s / s̈ (used in Chechen) is not encoded. The possibilities for such combinations seem limitless.

Moreover, what if a future language or a constructed language (人工語言), as seen in science fiction or linguistic experiments, required multiple diacritical marks on a single letter, such as an umlaut combined with an acute accent on o (this glyph used in Pinyin to represent /y/ with second tone) ? Would each new diacritical letter require a unique code point?

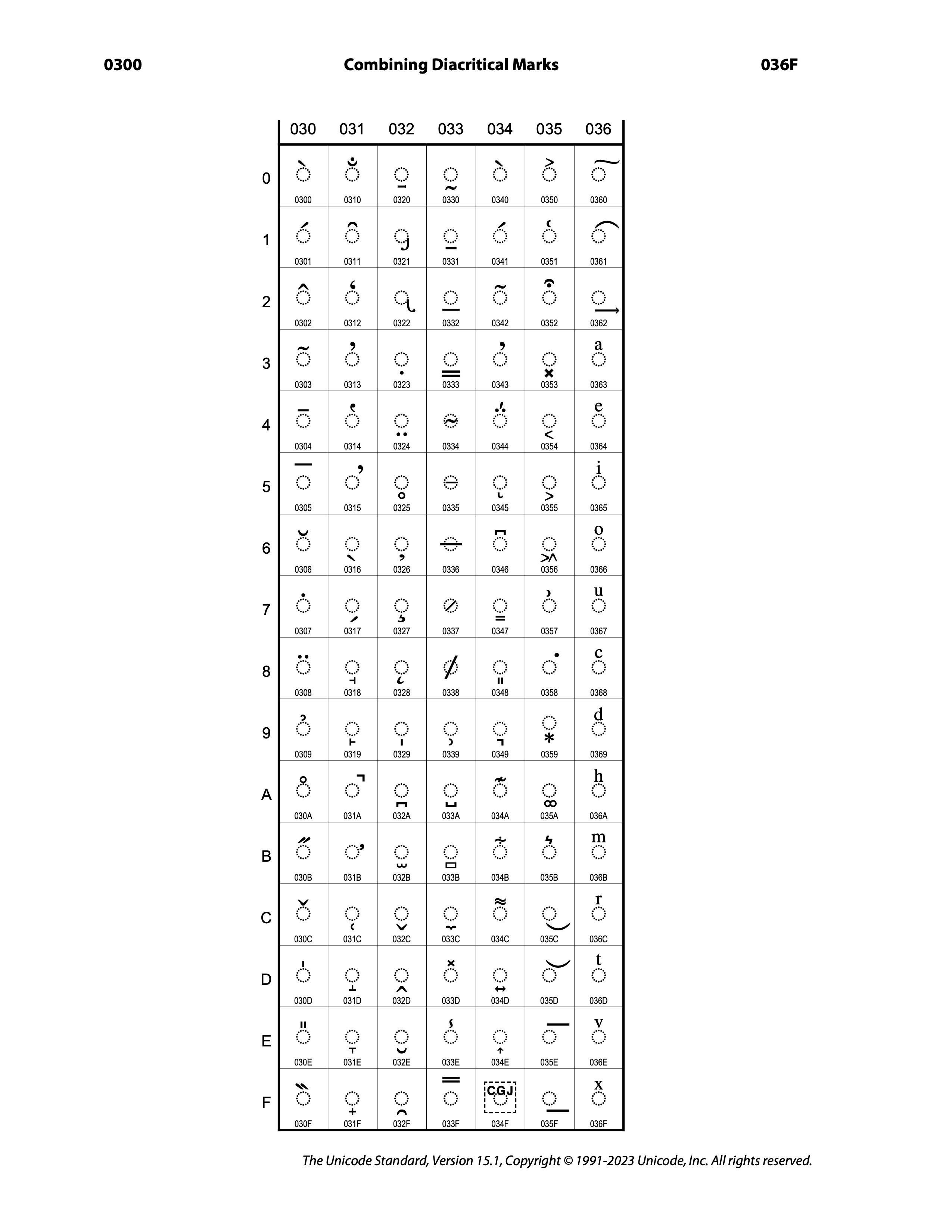

All combining diacritical marks encoded in Unicode. (Source: Unicode)

Unicode soon recognized that even with its huge number of code points (up to 1,114,112), it would be impossible to assign every possible combination of base letters and diacritical marks. This realization led to a give up from the one-letter-one-code-point principle.

Instead, Unicode decide to use a more flexible approach: using Character Combinations as solution. For example, the letter é (U+00E9) could be represented by the base Latin letter e (U+0065) followed by a combining acute accent ◌́ (U+0301).

This solution offers significant advantages. Even if a specific accented letter is not encoded in Unicode, it can still be represented by combining a base letter with one or more diacritical marks.

![]()

Basic Method: Just Put Letter & Diacritics Together

This flexibility also raises a new question: Without assigned code points for accented characters, how should fonts and typesetting engines accurately render these characters?

The simplest approach might be to show the base letter first, then followed by the diacritical mark. For instance, to display é, the typesetting engine could render an e first and then place a acute accent following.

However, the diacritical mark might appear misaligned, because the diacritical marks often carry their own width, the result can look like e followed by an acute accent separately, rather than a combined é.

Though users and readers might understand the purpose, it looks quite inharmony.

What if we try setting the width of diacritical mark to zero and shifting it left to align properly? Unfortunately, this might only work well with monospaced fonts, where every character has the same width. In proportional fonts, where letters like i and M have different widths, a diacritical mark that fits perfectly over i might appear strange when placed over M, and vice versa.

Moreover, this idea struggles when a single base letter is combined with multiple diacritical marks. Since the height and position of these marks are fixed, diacritics end up overlapping or misaligned.

Although the multiple code points with multiple glyphs method simplifies the display of diacritical letters with a basic typesetting engine that only needs to render the characters associated with each code point, the visual result is often less than ideal.

Advanced Method: Implementing Opentype Feature

For better display effect, we can implement OpenType ccmp (Glyph Composition/Decomposition) feature to handle the combinations.

The ccmp feature is essential for managing Complex Text Layout (CTL, 複雜文字編排), as it allows fonts to compose or decompose glyphs to meet specific needs. This feature is particularly useful for characters that are either not encoded in Unicode or need to be displayed using alternate forms.

At its core, ccmp operates by defining substitution rules within GSUB (Glyph Substitution) table of typeface. These rules dictate how certain sequences of characters should be replaced or combined to form new glyphs.

For instance, when the font includes the ccmp feature, it can automatically replace the sequence of e and ◌́ with the single é glyph, ensuring the correct appearance and positioning of the acute accent.

The ccmp feature is particularly advantageous in writing systems with multiple diacritics, such as Taiwanese Hokkien POJ mentioned above. For example, representing the sound /ɔ/ with a second tone requires an o with both an accent and a dot above it. By applying the ccmp feature, the typesetting engine can automatically substitute o (U+006F), ◌́ (U+0301), and ◌͘ (U+0358) with a composite glyph: oo-poj-acute, which is not encoded in Unicode.

This technology relies on the precise definition of glyph components and substitution rules within the font, enabling designers to create full-support typefaces that meet a wide range of writing system needs, including those that extend beyond standard Unicode encoding.

Setting up Opentype Features

Adobe Font Development Kit for OpenType (AFDKO) is a powerful tool to define and implement the Opentype feature in fonts by editing feature files (.fea).

First, we have to ensure our font contains all necessary base glyphs and diacritics for composition or decomposition. If you are working with oo-poj-acute we mentioned above, the font should include the base characters o (U+006F), diacritics ◌́ (U+0301) & ◌͘ (U+0358), and composite glyph oo-poj-acute.

With all glyphs ready, we can start defining the ccmp feature by AFDKO. Here’s a simple example of how to set up the ccmp feature:

feature ccmp {

# base ccmp

sub o dotaboverightcomb acutecomb by oo-poj-acute;

sub O dotaboverightcomb acutecomb by OO-poj-acute;

# same glyph, but reversed sequences

sub o acutecomb dotaboverightcomb by oo-poj-acute;

sub O acutecomb dotaboverightcomb by OO-poj-acute;

} ccmp;

AFDKO offers a powerful framework for defining and implementing the ccmp feature in fonts. By following the steps and defining well, we can effectively manage ccmp feature, enhancing the diversity and functionality of typefaces.

Unicode Equivalence & Normalization

Due to compatibility and historical reasons, Unicode does not remove existing encoded glyphs. Thus, even if a diacritical letter can be decomposed into a base Latin letter and multiple diacritical marks, such as é mentioned above, which can be represented as the sequence [ e (U+0065) with acute accent ◌́ (U+0301) ], the isolated é still keeps its assigned code point U+00E9.

For readers and users, characters with assigned code points and those using decomposed sequences should be considered the same. Both of Them should be treated as equivalent in comparisons, searches, and sorting.

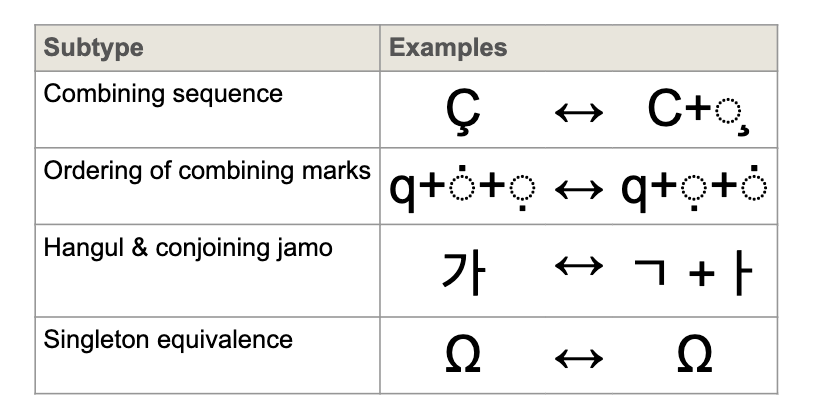

Unicode defines two types of equivalence: Canonical Equivalence and Compatibility Equivalence. Here, we are focus on the former. Canonical Equivalence refers to the fundamental equality between isolated character or sequences of characters that represent the same abstract entity, and which, when displayed correctly, should always express the same visual appearance.

Examples of Canonical Equivalence. (Source: Unicode)

For instance, according to the rules of Canonical Equivalence, é (U+00E9) and [ e (U+0065) + ◌́ (U+0301) ] should point to the same glyph. Similarly, [ o (U+006F) + ◌́ (U+0301) + ◌͘ (U+0358) ] (acute first, then dot above) and [ o (U+006F) + ◌͘ (U+0358) + ◌́ (U+0301) ] (dot above first, then acute) are also Canonical Equivalence, despite the differing order of combining marks, both should be regarded as the same glyph.

In practice, normalization and equivalence handling are managed by software and rendering engines, with varying levels of support. Some older operating systems or apps may not follow to Unicode standards, or engines may not support for OpenType features. This issue is particularly pronounced in the complex composed glyph.

Conclusion

My role in this project was not only technical but also cultural, as it directly contributes to preserving and making local linguistic heritage more accessible. By enabling these languages to be accurately represented in digital form, we help ensure they remain accessible for future generations.